- 1 Introduction

- 2 The Black Country 2039: Spatial Vision, Strategic Objectives and Strategic Priorities

- 3 Spatial Strategy

- 4 Infrastructure & Delivery

- 5 Health and Wellbeing

- 6 Housing

- 7 The Black Country Economy

- 8 The Black Country Centres

- 9 Transport

- 10 Environmental Transformation and Climate Change

- 11 Waste

- 12 Minerals

- 1 Sub-Areas and Site Allocations

- 2 Delivery, Monitoring, and Implementation

- 3 Appendix – changes to Local Plans

- 4 Appendix – Centres

- 5 Appendix – Black Country Plan Housing Trajectory

- 6 Appendix – Nature Recovery Network

- 7 Appendix – Glossary (to follow)

Draft Black Country Plan

(34) 10 Environmental Transformation and Climate Change

Introduction

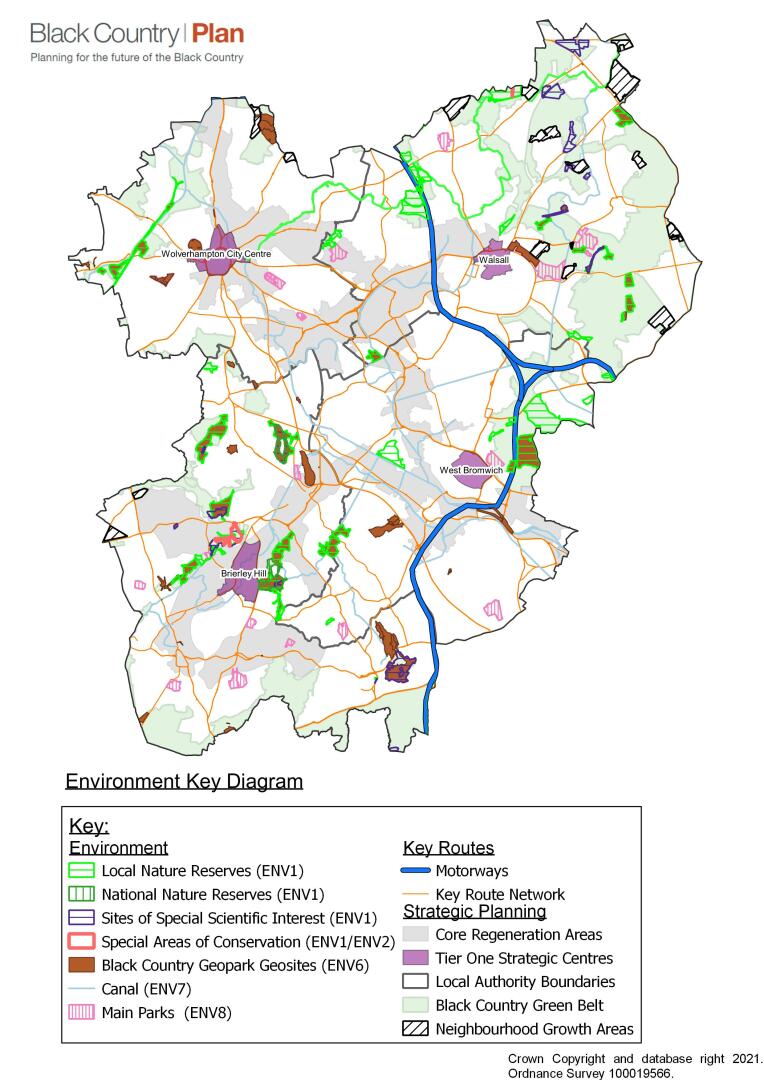

10.1 The Black Country enjoys a unique physical and cultural heritage thanks to its origins as a mainstay of heavy industry and driver of the Industrial Revolution. The geological complexity of the area, its topography, its settlement pattern and the existence of significant areas of green and open space within one of the most densely-developed parts of the country require a set of robust and relevant planning policies that will help to protect and enhance what gives the Black Country its unique physical, ecological and historic character and appearance.

10.2 The protection and improvement of the Black Country's biodiversity and geodiversity will improve the attractiveness of the area for people to live, work, study and visit while at the same time improving the physical and natural sustainability of the conurbation in the face of climate change. This will directly contribute to achieving Spatial Objectives 1, 2, 5, 6, 11 and 12.

10.3 The BCP addresses a number of established and emerging topic areas, including the natural and historic environments, air quality, flooding and climate change.

10.4 The chapter includes a specific section containing policies designed to mitigate and adapt to a changing climate, including policies on the management of heat risk, the use of renewable energy, the availability of local heat networks and the need for increasing resilience and efficiency to help combat the changes that are affecting people and the environment.

10.5 The importance of green infrastructure in achieving a healthy and stable environment is reflected throughout the plan and is supported in this chapter by policies on trees and environmental net gain.

10.6 The importance of the Black Country in terms of its contribution to geological science and the environment is recognised by its UNESCO Geopark status, which is also reflected in a policy for the first time.

10.7 The Black Country contains, or has the potential to impact on, several Special Areas of Conservation (including Cannock Chase). These sites are of European importance and the Black Country has a major role to play in ensuring their special environmental qualities are not impacted adversely by development.

Figure 10 - Environment Key Diagram

Nature Conservation - Spatial Objectives

10.8 The protection and improvement of the Black Country's biodiversity and geodiversity will safeguard and improve the environmental attractiveness and value of the area for residents and visitors while at the same time improving the physical and natural sustainability of communities within the conurbation in the face of climate change. This will directly contribute to delivering Strategic Priority 11, which is also associated with supporting the physical and mental wellbeing of residents.

(59) Policy ENV1 – Nature Conservation

- Development within the Black Country will safeguard nature conservation, inside and outside its boundaries, by ensuring that:

- development will not be permitted where it would, alone or in combination with other plans or projects, have an adverse impact on the integrity of an internationally designated site, including Special Areas of Conservation (SAC), which are covered in more detail in Policy ENV2;

- development is not permitted where it would harm nationally (Sites of Special Scientific Interest and National Nature Reserves) or regionally (Local Nature Reserves and Sites of Importance for Nature Conservation) designated nature conservation sites;

- locally designated nature conservation sites (Sites of Local Importance for Nature Conservation), important habitats and geological features are protected from development proposals that could negatively impact them;

- the movement of wildlife within the Black Country and its adjoining areas, through both linear habitats (e.g. wildlife corridors) and the wider urban matrix (e.g. stepping-stone sites) is not impeded by development;

- species that are legally protected, in decline, are rare within the Black Country or that are covered by national, regional, or local Biodiversity Action Plans will be protected as far as possible when development occurs.

- Adequate information must be submitted with planning applications for proposals that may affect any designated site or important habitat, species, or geological feature, to ensure that the likely impacts of the proposal can be fully assessed. Where the necessary information is not made available, there will be a presumption against granting permission.

- Where, exceptionally, the strategic benefits of a development clearly outweigh the importance of a local nature conservation site, species, habitat or geological feature, damage must be minimised. Any remaining impacts, including any reduction in area, must be fully mitigated. Compensation will only be accepted in exceptional circumstances. A mitigation strategy must accompany relevant planning applications.

- Over the plan period, the BCA will update evidence on designated nature conservation sites and Local Nature Reserves as necessary in conjunction with the Local Sites Partnership and Natural England and will amend existing designations in accordance with this evidence. Consequently, sites may receive new, or increased, protection over the Plan period.

- All appropriate development should positively contribute to the natural environment of the Black Country by:

- extending nature conservation sites;

- improving wildlife movement; and / or

- restoring or creating habitats / geological features that actively contribute to the implementation of Nature Recovery Networks, Biodiversity Action Plans (BAPs) and / or Geodiversity Action Plans (GAPs) at a national, regional, or local level.

- Details of how improvements (appropriate to their location and scale) will contribute to the natural environment, and their ongoing management for the benefit of biodiversity and geodiversity, will be expected to accompany planning applications.

- Local authorities will provide additional guidance on this in Local Development Documents and SPDs where relevant.

(5) Justification

10.9 The past development and redevelopment of the Black Country, along with Birmingham, has led to it being referred to as an "endless village"[24], which describes the interlinked settlements and patches of encapsulated countryside present today. The Black Country is home to internationally and nationally designated nature conservation sites and has the most diverse geology, for its size, of any area on Earth[25]. Many rare and protected species are found thriving within its matrix of greenspace and the built environment.

10.10 The Black Country lies at the heart of the British mainland and therefore can play an important role in helping species migrate and adapt to climate change as their existing habitats are rendered unsuitable. It is therefore very important to increase the ability of landscapes and their ecosystems to adapt in response to changes in the climate by increasing the range, extent, and connectivity of habitats. In order to protect vulnerable species, the Nature Recovery Network process, which is taking place at a national level, will allow isolated nature conservation sites to be protected, buffered, improved, and linked to others. This will be supplemented by the emerging Black Country Nature Recovery Network Strategy, which all development will be required to consider as set out under Policy ENV3. Species dispersal will be aided by extending, widening, and improving the habitats of wildlife corridors. Conversely, fragmentation and weakening of wildlife sites and wildlife corridors by development will be opposed.

10.11 Development offers an opportunity to improve the local environment and this is especially so in an urban area. The BCA are committed to meeting their "Biodiversity Duty" under the Natural Environment and Rural Communities Act (2006) and to delivering the principles of the NPPF by proactively protecting, restoring and creating a richer and more sustainable wildlife and geology.

10.12 The local Biodiversity Partnership, Geodiversity Partnership and Local Sites' Partnership will identify, map, and regularly review the priorities for protection and improvement throughout the Black Country, in accordance with the emerging Black Country Nature Recovery Network strategy. These will be used to inform planning decisions.

(2) Primary Evidence

- Birmingham and Black Country EcoRecord

- Birmingham and Black Country Local Sites Assessment Reports

- Biodiversity Action Plan for Birmingham and the Black Country (2009)

- Geodiversity Action Plan for the Black Country (2005)

- An Ecological Evaluation of the Black Country Green Belt (2019)

(2) Delivery

- Biodiversity and Geodiversity Action Plans.

- Development and implementation of Black Country Nature Recovery Network

- Updated ecological surveys and Local Sites Assessment Reports, as appropriate.

- Preparation of Local Development Documents.

- Development Management process.

Issues and Options consultation response

10.13 Policy ENV1 has worked effectively to protect and enhance biodiversity

10.14 Support from a number of respondents for including ancient woodland in list of nationally designated sites

10.15 The Policy should allow for appropriate mitigation or off-setting so that development sites are not sterilised unduly

10.16 The overall consensus from issues and options was that ENV1 worked well at protecting nature conservation and could be strengthened with the addition of reference to ancient woodlands,

Special Areas of Conservation

10.17 There are a number of Special Areas of Conservation (SAC) within and close to the Black Country which may be adversely affected by development within the Black Country over the Plan period. A policy approach is required to address any identified potential impacts.

(19) Policy ENV2 - Development Affecting Special Areas of Conservation (SACs)

Cannock Chase SAC

- An appropriate assessment will be carried out for any development that leads to a net increase in homes or creates visitor accommodation within 15 km of the boundary of Cannock Chase SAC, as shown on the Policies Maps for Walsall and Wolverhampton.

- If the appropriate assessment determines that the development is likely to have an adverse impact upon the integrity of Cannock Chase SAC, then the developer will be required to demonstrate that sufficient measures can be provided to either avoid or mitigate the impact.

- Acceptable mitigation measures will include proportionate financial contributions towards the current agreed Cannock Chase SAC Partnership Site Access Management and Monitoring Measures (SAMMM).

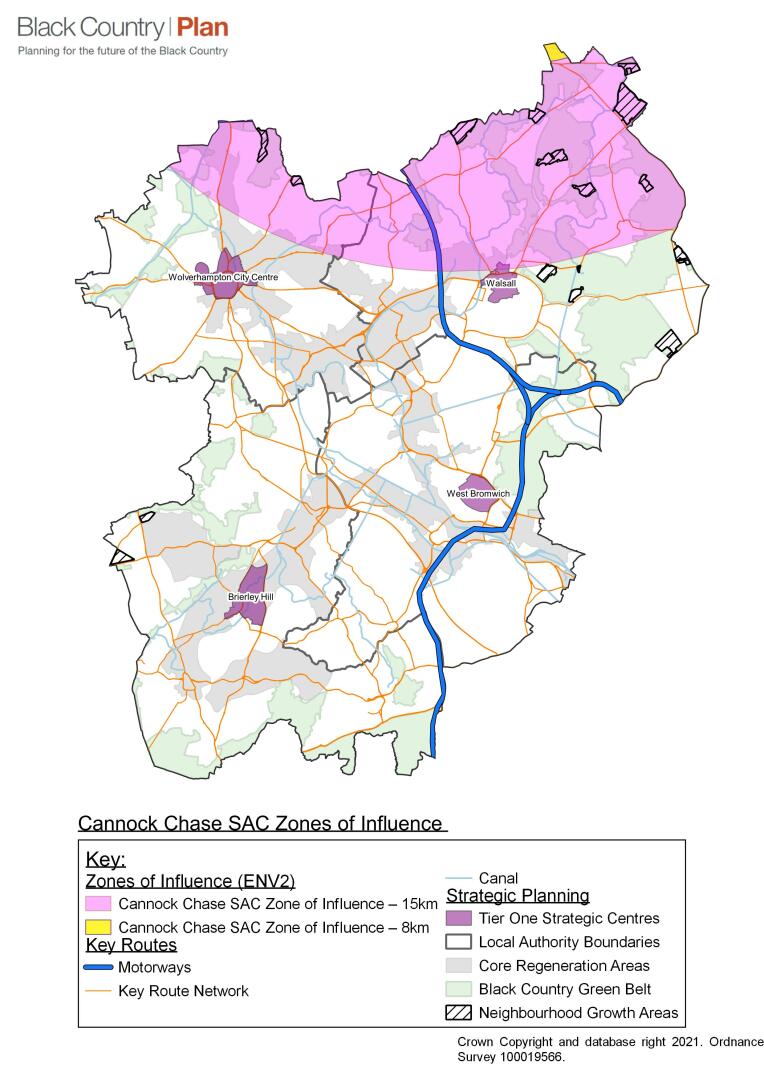

Figure 11 - Cannock Chase SAC

(2) Justification

10.18 There are a number of Special Areas of Conservation (SAC) within and close to the Black Country. Fens Pool SAC is located in Dudley and the Cannock Extension Canal extends between Walsall and Cannock. Cannock Chase SAC, located to the north of the Black Country, is one of the best areas in the UK for European dry heath land and is the most extensive area of dry heath in the Midlands.

Cannock Chase SAC

10.19 Walsall and Wolverhampton Councils are part of the Cannock Chase SAC Partnership, which works together to prevent damage to the SAC. Other members of the Partnership include Natural England, Staffordshire County Council, Cannock Chase District Council, Lichfield District Council, East Staffordshire Borough Council, South Staffordshire District Council, the Forestry Commission and the Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONB) Partnership. A key role of the Partnership is to ensure no adverse effect on the integrity of the SAC arises from new housing development via recreational pressure.

10.20 A Visitor Survey and Planning Evidence Base Review (PEBR) completed by the Partnership during 2019-21 demonstrated that any development within 15 km of Cannock Chase SAC that could increase visitor use of Cannock Chase may have a significant impact on the integrity of the SAC. The PEBR recommended a package of Site Access Management and Monitoring Measures (SAMMM), which are considered necessary to mitigate the cumulative impact of maximum potential housing development within the 15 km zone up to 2040. These measures include habitat management and creation; access management and visitor infrastructure; publicity, education and awareness raising; provision of additional recreational space within development sites where they can be accommodated; and measures to encourage sustainable travel. Completion of an updated Cannock Chase SAC Partnership Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) to reflect this new evidence is anticipated by 2022.

10.21 Parts of northern Walsall and Wolverhampton, as shown on Figure 11 and the Policies Maps, fall within 15 km of Cannock Chase SAC. Any development within this area over the Plan period that results in new homes or creates visitor accommodation, such as a hotel or caravan site, may lead to adverse effects on the SAC through increased visitor activities. Therefore, Walsall and Wolverhampton Councils will seek contributions towards the total cost of the Cannock Chase SAC SAMMM in proportion to the amount of housing development anticipated to take place within the 15 km zone.

10.22 Given the significantly higher frequency of visits to Cannock Chase SAC from households living within 8 km of the SAC, a higher level of contributions may be sought from housing developments within this zone. Also, given the need to create an effective contributions system that secures a reasonable minimum level of contributions from each development, it is likely that, within the Black Country, only developments of ten homes or more will be expected to make a payment towards the Cannock Chase SAC SAMMM. Guidance will be produced to set out the detailed procedure and the level of financial contributions required. This guidance will come into effect following completion of the MOU.

10.23 Policy ENV2, supported by guidance, will ensure that decisions made on planning applications in the Black Country will not have adverse effects on Cannock Chase SAC. If there are any potential adverse impacts, the development must be refused unless there are appropriate mitigation measures in place. Any proposals that comply with the current guidance are likely to result in a conclusion of no adverse impact on the integrity of Cannock Chase SAC.

Nitrous Oxide (NOx) Deposition

10.24 A number of different types of development can increase the levels of Nitrous Oxide (NOx) deposition that may affect designated SACs, both directly (via increasing industrial emissions) or indirectly (for example, via increasing traffic usage on main roads that run within close proximity of the boundary of the SAC). Where it is possible that a development may result in harm to a SAC by significantly increasing the level of NOx deposition, then the relevant Council will carry out an appropriate assessment and may require the developer to provide sufficient measures to either avoid or mitigate adverse impacts.

10.25 A partnership approach is being developed to address NOx deposition impacts on SACs in the West Midlands area. When the Partnership is established, evidence collected, and a system developed to address NOx deposition avoidance and mitigation, it is anticipated that this will provide an effective mechanism to deal with NOx impacts, similar to that developed for Cannock Chase SAC visitor impacts.

Fens Pools SAC

10.26 The Fens Pools SAC extends to approximately 20 hectares and is located in Dudley. The site comprises three canal feeder reservoirs and a series of smaller pools and a wide range of other habitats from swamp, fen and inundation communities to unimproved neutral and acidic grassland and scrub. Great crested newts (Triturus cristatus) occur as part of an important amphibian assemblage which comprises the qualifying species feature of the SAC.

10.27 Fens Pools SAC is sensitive to changes in air quality and vulnerable to water pollution, as these may affect nutrient neutrality at the site. The Habitats Regulations Assessment Screening of the draft BCP has concluded that further evidence is needed on current air quality and modelling of potential traffic movements close to the site before a conclusion can be drawn on the potential impact of the draft BCP proposals on Fens Pool SAC and any necessary policy response. This evidence will be available to inform the Publication BCP and may require the inclusion of a specific approach in Policy ENV2. Habitat fragmentation has been identified as a threat to the 'great crested newt' qualifying feature of the site.

Cannock Extension Canal SAC

10.28 The Cannock Extension Canal SAC covers an area of approximately 5.47 hectares and is partially situated within north Walsall. It is an example of anthropogenic, lowland habitat that is fed by the Chasewater Reservoir SSSI. Its qualifying feature is floating water-plantain (Luronium natans) and the canal supports the eastern limit of the plant's natural distribution in England. A very large population of the species occurs in the canal, which has a diverse aquatic flora and rich dragonfly fauna, indicative of good water quality.

10.29 Air quality has been identified as a threat to the 'floating water-plantain' qualifying feature of Cannock Extension Canal SAC. Of particular concern is atmospheric nitrogen deposition and ground level ozone. The Habitats Regulations Assessment Screening of the draft BCP has concluded that further evidence is needed regarding air quality and modelling of potential traffic movements close to the site before a conclusion can be drawn on the potential impact of the draft BCP proposals and any necessary policy response. This evidence will be available to inform the Publication BCP.

(1) Evidence

- Cannock Chase SAC Planning Evidence Base Review: Stage 1 (Footprint Ecology, 2018)

- Cannock Chase Visitor Survey (Footprint Ecology, 2018)

- Cannock Chase SAC Planning Evidence Base Review: Stage 2 (Footprint Ecology, 2021)

- Habitats Regulations Assessment Screening of Draft Black Country Plan (Lepus, 2021)

- Draft Black Country Plan Duty to Cooperate Statement (2021)

(1) Delivery

- Completion of Cannock Chase SAC Partnership Memorandum of Understanding

- Preparation of Cannock Chase SAC Mitigation Guidance for Wolverhampton and Walsall

- Completion of air quality and transport modelling evidence for Fens Pool SAC

- Development Management process

Issues and Options Consultation Responses

10.30 Respondents requested that the Plan should make reference to the updated evidence base on Cannock Chase SAC (CCSAC) and include a policy to address CCSAC issues to align with other CCSAC Partnership authorities.

Nature Recovery Network and Biodiversity Net Gain

10.31 The Nature Recovery Network (NRN) is a major commitment in the government's 25 Year Environment Plan. The Government has set out in the Environment Bill 2019 - 21 that a Local Nature Recovery Strategy (LNRS) is to be prepared locally and published for all areas of England, and that these will:

a) agree priorities for nature's recovery;

b) map the most valuable existing habitat for nature using the best available data; and

c) map specific proposals for creating or improving habitat for nature and wider environmental goals.

10.32 LNRS will help restore many ecosystem functions and improve the services upon which society depends, benefitting nature, people and the economy, and helping to address three of the biggest challenges society faces: biodiversity loss, climate change and human wellbeing.

10.33 LNRS will support delivery of mandatory biodiversity net gain and provide a focus for a strengthened duty on all public authorities to conserve and enhance biodiversity, which is also being introduced by the Bill. They will underpin the Nature Recovery Network, alongside work to develop partnerships and to integrate nature into incentives and land management actions.

10.34 Biodiversity net gain is a process that attempts to leave the environment in a more valuable and richer condition than it was found to be in previously. The Government has set out in the Environment Bill 2019 - 21 that development proposals are required to provide a minimum 10% uplift in habitat quality where sites are being developed.

10.35 This process involves the use of a metric as a proxy for recognising the negative impacts on habitats arising from a development and calculating how much new or restored habitat, and of what types, is required to deliver sufficient net gain.

10.36 The Environment Bill 2019 - 21 is scheduled to progress to the draft legislation stage and be laid before Parliament in Autumn 2022. Policy ENV3 sets out how development proposals would be required to consider the Nature Recovery Network Strategy and how biodiversity net gain would be secured

(52) Policy ENV3 – Nature Recovery Network and Biodiversity Net Gain

- All development shall deliver the Local Nature Recovery Network Strategy in line with the following principles:

- take account of where in the Local Nature Recovery Network the development is located and deliver benefits appropriate to that zone;

- follow the mitigation hierarchy of avoidance, mitigation and compensation, and provide for the protection, enhancement, restoration and creation of wildlife habitat and green infrastructure;

- follow the principles of Making Space for Nature and recognise that spaces are needed for nature and that these should be of sufficient size and quality and must be appropriately connected to other areas of green infrastructure, to address the objectives of the Black Country Nature Recovery Network Strategy.

- All development shall deliver a minimum 10% net gain in biodiversity value when measured against baseline site information.

- Losses and gains as a result of proposed development will be calculated using the national Biodiversity Metric.

- Development that is likely to have an impact on biodiversity will be considered in accordance with the mitigation hierarchy set out in the NPPF.

- Biodiversity net gain shall be provided in line with the following principles:

- a preference for on-site habitat provision / enhancement wherever practicable, followed by improvements to sites within the local area, and then other sites elsewhere within the Black Country;

- the maintenance and where possible enhancement of the ability of plants and animals (including pollinating insects) to move, migrate and genetically disperse across the Black Country;

- the provision / enhancement of priority habitats identified at the national, regional, or local level, having regard to the scarcity of that habitat within the Black Country;

- Exemptions to the need to provide biodiversity net gain on all development will be as set out in the relevant legislation and national guidance.

- Compensation will only be accepted in exceptional circumstances. Provision of off-site compensation should not replace or adversely impact on existing alternative / valuable habitats in those locations and should be provided prior to development.

Justification

10.37 Locally developed Nature Recovery Network strategies are due to be introduced through the Environment Bill. LNRS will help to map the NRN locally and nationally, and will help to plan, prioritise and target action and investment in nature at a regional level across England.

10.38 The Environment Bill (when enacted) will introduce a new duty on all public bodies to have regard to any relevant LNRSs, creating an incentive for a wide range of organisations to engage with the creation of LNRSs and to take steps to support their delivery. Local authorities and other public bodies designated by the Secretary of State will also have to report on what steps they have taken, at least every five years.

10.39 The Black Country Authorities have commenced work on a Local Nature Recovery Network Strategy. This has produced draft opportunities mapping that future development proposals will be required to consider in demonstrating how they deliver benefits appropriate to the zones identified. The draft Nature Recovery Network Opportunities Map (April 2021) is shown at Appendix 18 alongside a description of the components of the opportunities map.

10.40 The Environment Bill underpins the government's approach to establishing the NRN. The Environment Bill: sets the framework for at least one legally binding biodiversity target; establishes spatial mapping and planning tools to identify existing and potential habitat for wildlife and agrees local priorities for enhancing biodiversity in every area of England (LNRS); creates duties and incentives, including mandatory biodiversity net gain.

10.41 Biodiversity net gain has been described as a measurable target for development projects where impacts on biodiversity are outweighed by a clear mitigation hierarchy approach to first avoid and then minimise impacts, including through restoration and / or compensation.

10.42 Net gain is an approach to development, and / or land management, which aims to leave the natural environment in a measurably better state than beforehand (DEFRA Biodiversity Metric 2.0 Dec 2019).

10.43 Mandatory biodiversity net gain will provide a financial incentive for development to support the delivery of LNRSs through an uplift in the calculation of biodiversity units created at sites identified by the strategy. LNRSs have also been designed to help local planning authorities deliver existing policy on conserving and enhancing biodiversity and to reflect this in the land use plans for their area.

10.44 The Environment Bill 2019 - 21 proposes that new developments must demonstrate a minimum 10% increase in biodiversity on or near development sites. New development should always seek to enhance rather than reduce levels of biodiversity present on a site. This will require a baseline assessment of what is currently present, and an estimation of how proposed designs will add to that level of biodiversity, supported by evidence that a minimum 10% net gain has been delivered.

10.45 Development generates opportunities to help achieve an overall nature conservation benefit. It will often be possible to secure significant improvements through relatively simple measures, such as the incorporation of green infrastructure and features including bird / bat boxes and bricks that can enable wildlife to disperse throughout the Black Country.

10.46 Biodiversity features of value frequently occur beyond designated sites and should be conserved, enhanced and additional features created as part of development.

10.47 On-site biodiversity improvements will also be vital to enhancing the liveability of urban areas, and improving the connection of people to nature, particularly as development densities increase. Development should also contribute to wildlife and habitat connectivity in the wider area, in line with the Biodiversity Action Plan and the developing Black Country Local Nature Recovery Strategy.

10.48 The ways in which developments secure a net gain in biodiversity value will vary depending on the scale and nature of the site. On some sites, the focus will be on the retention of existing habitats. For others, this may be impracticable, and it may be necessary instead to make significant provision for new habitats either on- or off-site.

10.49 It can be challenging to establish new habitats. It is essential that the most important and irreplaceable habitats in the Black Country are protected, and so mitigation rather than retention will not be appropriate in some circumstances.

Evidence

- The Environment Bill 2019 – 2021

- The Government's 25 Year Environment Plan

- Nature Networks Evidence Handbook - Natural England Research Report NERR081

- Making Space for Nature (Lawton et al. 2010)

- DEFRA Biodiversity Metric 2.0 (Dec 2019)

- Biodiversity Net Gain – Principles and Guidance for UK Construction and Developments – CIEEM

Delivery

- Development Management, legal and funding mechanisms.

(2) Issues and Options Consultation Responses

10.50 This is a new policy produced in response to emerging national legislation and thus was not addressed previously.

Provision, retention and protection of trees, woodlands, and hedgerows

10.51 The BCA will support and protect a sustainable, high-quality tree population and will aim to significantly increase tree cover across the area over the Plan period.

10.52 A main theme of the Government's 25-Year Environment Plan is the need to plant more trees. This is to be achieved not only as part of the creation of extensive new woodlands but also in urban areas; this will be accomplished in part by encouraging businesses to offset their emissions in a cost-effective way through planting trees. The national ambition is to deliver one million new urban trees and a further 11 million new trees across the country.

10.53 It is important to encourage and support the delivery of green infrastructure and ecological networks through urban areas, especially in relation to their role in climate change mitigation and adaptation and to mitigate the health problems associated with air pollution. The provision of new trees and the protection of existing ones throughout the Black Country will be a key component of this approach.

10.54 The aim will be to increase the Black Country's canopy cover to at least 18% over the plan period[26], based on data establishing its current levels of provision[27] and identifying opportunities for doing so derived from the Nature Recovery Network and biodiversity net gain targets.

(46) Policy ENV4 – Provision, retention and protection of trees, woodlands and hedgerows

Retention and protection of trees and woodland

- Development that would result in the loss of or damage to ancient trees, ancient woodland or veteran trees will not be permitted. Development adjacent to ancient woodland will be required to provide an appropriate landscaping buffer, with a minimum depth of 15m and a preferred depth of 50m.

- Provision should also be made for the protection of individual veteran or ancient trees likely to be impacted by development, by providing a buffer around such trees of a minimum of 15 times the diameter of the tree. The buffer zone should be 5m from the edge of the tree’s canopy if that area is larger than 15 times its diameter.

- There will be a presumption against the removal of trees that contribute to public amenity and air quality management unless sound arboricultural reasons support their removal[28]. Where removal is unavoidable, replacement trees should be provided to compensate for their loss, on a minimum basis of three for one.

- The planting of new, predominantly native, trees and woodlands will be sought, in appropriate locations, to increase the extent of canopy cover in the Black Country to around 18% over the period to 2039.

- Tree Preservation Orders will be used to protect individual(s) or groups of trees that contribute to the visual amenity and / or the character of an area and that are under threat of damage or removal.

Habitat Creation

- All available data on extant tree cover and associated habitat[29] will be considered when making decisions on the proposed loss of trees and woodland to accommodate infrastructure and other development proposals. In areas where evidence demonstrates that current levels of tree cover are low, proposals that incorporate additional tree planting, to increase existing levels of habitat and canopy cover, will be considered positively, as part of the wider contribution to biodiversity net gain.

- A majority of native tree species able to withstand climate change should be used in landscaping schemes or as replacement planting, to maximise habitats for local wildlife / species and maintain and increase biodiversity. In circumstances where non-native tree species are also considered to be appropriate, a mix of native and non-native species should be provided, to help maintain a healthy and diverse tree population.

- Opportunities for increasing tree provision through habitat creation and the enhancement of ecological networks, including connecting areas of ancient woodland, will be maximised, in particular by means of the biodiversity net gain and nature recovery network initiatives (see Policy ENV3).

Trees and development

- An arboricultural survey, carried out to an appropriate standard, should be undertaken prior to removal of any vegetation or site groundworks and used to inform a proposal’s layout at the beginning of the detailed design process.

- Development should be designed around the need to incorporate trees already present on site, using sensitive and well-designed site layouts to maximise their retention.

- Existing mature trees[30], trees that are ecologically important, and ancient / veteran trees, must be retained and integrated into the proposed landscaping scheme, recognising the important contribution of trees to the character and amenity[31] of a development site and to local green infrastructure networks.

- In addition to meeting the requirements for replacement trees on sites and biodiversity net gain, new tree planting should be included in all new residential developments and other significant proposals[32], as street trees or as part of landscaping schemes. Development proposals should use large-canopied species where possible, which provide a wider range of health, biodiversity and climate change mitigation and adaptation benefits because of their larger surface area and make a positive contribution to increasing overall canopy cover[33].

- New developments should make a minimum contribution of 20% canopy cover across the development site and a recommended contribution of 30% canopy cover across the development site[34].

- New houses and other buildings must be carefully designed and located to prevent an incompatible degree of shade[35] being cast by both existing and new trees that might result in future pressure for them to be removed.

- The positioning of trees in relation to streets and buildings should not worsen air quality for people using and living in them. Care should be taken to position trees and / or design streets and buildings in a way that allows for street-level ventilation to occur, to avoid trapping pollution between ground level and tree canopies (see Policy CC4).

- Where planning permission has been granted that involves the removal of trees, agreed replacement trees of a suitable species must be provided onsite. Where sufficient and suitable onsite replacements cannot be provided, off-site planting or woodland enhancement, including support for natural regeneration, in the near vicinity of the removed tree(s) must be provided, in line with the mitigation hierarchy set out in Policy ENV3. Appropriate planning conditions will be used to secure timely and adequate alternative provision and ongoing maintenance.

- Replacement trees located off-site should not be planted where they would impact on areas designated as ecologically important unless this has been specifically agreed with the relevant authority and its ecological officers / advisers.

- Trees proposed for removal during development should be replaced at a ratio of at least three for one. The species, size and number of replacement trees will be commensurate with the size, stature, rarity, and public amenity of the tree(s) to be removed. Where trees to be replaced form a group of amenity value (rather than individual specimens), replacement must also be in the form of a group commensurate with the area covered, size and species of trees and established quality of the original group and, where possible, located in a position that will mitigate the loss of visual amenity associated with the original group[36].

- Trees on development sites must be physically protected during development. Care must be taken to ensure that site engineering / infrastructure works[37], the storage of plant and machinery, excavations and new foundations do not adversely impact their continued retention, in line with current arboricultural and Building Regulation requirements.

- New trees on development sites should be planted in accordance with arboricultural best practice, including the use of suitably sized planting pits[38], supporting stakes, root barriers, underground guying, and appropriate protective fencing during the construction phase.

- Appropriate conditions will be included in planning permissions to ensure that new trees that fail on development sites are replaced within a specified period by trees of a suitable size, species, and quality.

- Where proposed development will impact on the protection, safety and / or retention of a number of trees, or on the character and appearance of trees of importance to the environment and landscape, the use of an arboricultural clerk of works[39] will be required, to be made subject to a condition on the relevant planning permission.

- A presumption should be applied that replacement trees are UK and Ireland sourced and grown, to help limit the spread of tree pests and diseases, while supporting regional nurseries where possible when acquiring them. Hedgerows

- There will be a presumption against the wholesale removal of hedgerows for development purposes, especially where ecological surveys have identified them to be species-rich and where they exist on previously undeveloped land.

- Hedgerow retention and reinforcement will be of particular importance where hedgerows form part of an established ecological network enabling the passage of flora and fauna into and out of rural, suburban, and urban areas. If hedgerow removal is needed to accommodate a high-quality site layout, replacement hedgerow planting will be required.

- Protection of hedgerows before and during development must be undertaken. This will include: the provision of landscape buffers where appropriate; protective fencing; and careful management of plant and materials on site to avoid damage to the hedgerow(s) and its root system.

- New hedgerows will be sought as part of site layouts and landscaping schemes.

(3) Justification

10.55 Section 15 of the NPPF (2019) identifies the importance of trees in helping to create an attractive and healthy environment. The NPPF expects local plans to identify, map and safeguard components of ecological networks and promote their conservation, restoration, and enhancement. Ancient woodlands and ancient and veteran trees are an irreplaceable aspect of both the ecological and historic landscape and the NPPF is very clear about the need to protect such resources where they occur. Hedgerows are also a finite and vulnerable resource and their provision, retention and enhancement will be expected when new development is proposed.

10.56 Tree canopy cover across the Black Country is currently 13.6%, using information from local and national sources that is regularly updated. The % canopy cover is available at a ward level[40], and varies across the Black Country. There is a need to increase total tree canopy cover to 18%, to help prevent the further fragmentation of habitats across the Black Country, support the Nature Recovery Network, and provide more equal canopy cover across all wards.

10.57 Wildlife corridors are important in helping overcome habitat fragmentation, by ensuring that species can reach the resources they need and that their populations do not become isolated, inbred, and prone to the adverse impacts of climate change. Supporting wildlife corridors will mean:

a) creating and maintaining a diverse tree population (including trees of all ages and sizes),

b) controlling invasive species,

c) promoting the reintroduction of native species in locations where they are appropriate and would have a positive impact on biodiversity,

d) retaining dead wood,

e) making sure that any new planting is in the right location and of the right species, and

f) recognising that woodlands are not simple monoculture habitats and will also contain glades, wet areas, understoreys, and grassland.

10.58 The requirement to plant trees on development sites will also help support and deliver increased biodiversity and green network opportunities on sites that at present do not contain tree cover, e.g. some sites currently in managed agricultural use where trees and hedgerows have previously been removed.

10.59 An example of the importance of trees in helping to manage and mitigate adverse impacts relating to air quality and climate change can be found in the report produced for the London iTree[41] project in 2015 (highlighting the value of London's tree population). This identified that the tree population of inner and outer London (8.5 million trees) held nearly 2.4 million tonnes of carbon and was sequestering an additional 77,000 tonnes per annum, equivalent to the total amount of carbon generated by 26 billion vehicle miles. The project also reported significant value and benefits provided by trees in terms of pollution removal, storm water alleviation, building energy savings and amenity.

10.60 The loss of trees from urban environments has been demonstrated to have negative outcomes for human health. Social costs, such as an increase in crime, have also been associated with the loss of trees[42]. There is a growing body of evidence that the presence of trees in and around urban environments provides major public health and societal benefits.

10.61 Trees in the urban landscape have a vital role to play in delivering ecosystem services[43], such as in:

a) helping to improve residents' physical health[44]

b) helping to improve residents' mental health by reducing stress levels

c) helping to mitigate climate change by sequestering carbon dioxide

d) providing shading and cooling benefits (including associated savings to the NHS from avoided skin cancer and heat stroke[45])

e) improving air quality and reducing atmospheric pollution

f) reducing wind speeds in winter, thereby reducing heat loss from buildings

g) reducing noise

h) Improving local environments and bringing people closer to nature

i) supporting ecological networks and green infrastructure

j) maximising people's enjoyment of and benefits from their environment

k) contributing towards the aesthetic value of the urban area

Trees on development sites

10.62 The BCP is delivering a significant quantum of new development and redevelopment in both urban and semi-rural areas and it will be important to ensure that the existing stock of trees and woodlands is protected, maintained, and expanded as far as possible. Developers will be expected to give priority to the retention of trees and hedgerows on development sites, and existing landscaping should also be kept and protected where possible.

10.63 There will be a requirement to: -

a) replace trees and woodlands that cannot be retained on development sites with a variety of suitable tree specimens (species and size);

b) require developers to both retain trees on sites as part of comprehensive landscape schemes and to provide suitable new trees in locations that will enhance the visual amenity of a development;

c) where individual or groups of trees are of landscape or amenity value, they are retained and that developments are designed to fit around them;

d) encourage diversity in the tree population to help to counter ecological causes of tree loss, such as diseases, pests, or climate change; and

e) balance the impacts of the loss of trees on climate change and flooding by identifying opportunities to plant replacements via appropriate tree and habitat enhancement and creation schemes.

10.64 As part of the requirement for biodiversity net gains (see Policy ENV3) developers and others will need to pursue adequate replacements for trees and woodlands lost to allocated and approved development, as well as additional trees and other habitat creation to achieve appropriate compensatory provision on sites. The main imperative will be to ensure that trees are maintained in good health on development sites in the first instance but where this is not possible, the grant of planning permission will be conditional upon the replacement and enhancement of tree cover nearby.

10.65 Tree species specified in submitted planting plans should be evaluated by either a chartered Landscape Architect or accredited arboriculturist employed by the local authority. This will ensure that a suitable variety of species and standard / size of tree is being planted and will deliver the most appropriate solution for a specific location.

10.66 Normally, for every tree removed from a development site a minimum of three replacement trees will be required to be planted on the site. There will be circumstances where the ratio of replacement planting will be greater than this – especially in cases where significant / mature trees contributing to the visual and ecological amenity of an area and its character are to be removed. Where a development site cannot accommodate additional planting, replacement trees will be expected to be planted in an appropriate off-site location.

10.67 The clearance of trees from a site prior to the submission of a planning application is discouraged. If the Local Planning Authority have robust evidence to prove that trees were until recently present on a cleared site, there will still be a requirement to provide suitable and sufficient replacement trees, either within the proposed scheme or on an alternative identified site. This is also addressed in the amended Environment Bill 2019 - 2021, which makes provision for sanctions against the clearance of sites prior to a planning application being submitted in relation to the requirement for biodiversity net gain.

10.68 To ensure that good tree protection measures are maintained through the construction project, the BCA will support and encourage the use of arboriculture clerks of work on development sites where trees are to be managed, removed and / or planted on the site. Where the likelihood of trees being adversely affected by construction activity is significant, the BCA will use appropriate conditions to require this level of oversight.

Ancient woodland and veteran trees[46]

10.69 The NPPF defines ancient woodland and veteran trees as an irreplaceable habitat. Ancient woodland is an area that has been wooded continuously since at least 1600 AD. It includes ancient semi-natural woodland and plantations on ancient woodland sites. An ancient or veteran tree is a tree which, because of its age, size, and condition, is of exceptional biodiversity, cultural or heritage value. Veteran trees are of exceptional value culturally, in the landscape, or for wildlife, due to their great age, size or location. The soils in which these trees sit has been identified as having a high biodiversity value, given the length of time the trees have been successfully established.

10.70 Individual trees can have historic and cultural value and can be linked to specific historic events or people, or they may simply have importance because of their appearance, contribution to landscape character and local landmark status. Some heritage trees may also have great botanical interest, for example as rare native trees or cultivars of historic interest.

10.71 Very few trees of any species can be classed as ancient or veteran. Such trees / areas are a finite resource of great biodiversity value. For this reason, the BCA consider that it is essential to provide absolute protection for ancient and veteran trees and ancient woodland sites in the Black Country.

Hedgerows

10.72 The planting of hedgerows not only enhances opportunities for wildlife but can also significantly improve the appearance of new development. It is particularly suitable on frontages and along plot and site boundaries, both softening the appearance of the built form and supplementing the design of the overall scheme.

10.73 Hedgerows are integral to ecological networks, given their linear form, and will be essential elements of habitat linkages within and beyond the Black Country. Planting additional hedgerows will help to support and increase the movement of wildlife and plants through the Black Country. The planting of bare root plants is an economical way of providing green infrastructure on sites.

(2) Evidence

- Valuing London's Urban Forest - Results of The London I-Tree Eco Project 2015

- Neighbourhood Greenspace and Health in A Large Urban Center. Sci. Rep. 5, 11610; Doi: 10.1038/Srep11610 (2015)

- Health Benefits of Street Trees - Vadims Sarajevs, The Research Agency Of The Forestry Commission, 2011

- GB Wards Canopy Cover Map

- GB 25-Year Environment Plan

- The Environment Bill 2019 - 2021

Delivery

- Development Management, legal and funding mechanisms.

Issues and Options Consultation Responses

10.74 This is a new policy produced in response to emerging national legislation and thus was not addressed previously.

Historic Character and Local Distinctiveness of the Black Country

10.75 Environmental transformation and promoting sustainable development are two of the underpinning themes of the Black Country Plan Vision, which in turn requires a co-ordinated approach to the conservation and enhancement of the built and natural environment. The protection and promotion of the historic character and local distinctiveness of the Black Country's buildings, settlements and landscapes are key elements of sustainability and transformation and in particular help to deliver Strategic Priority 12, to protect, sustain and enhance the quality of the built and historic environment, whilst ensuring the delivery of distinctive and attractive places.

10.76 Local distinctiveness arises from the cumulative contribution made by many and varied features and factors, both special and commonplace. It is the ordinary and commonplace features of the Black Country that, in fact, give it its distinctiveness and help to create a unique sense of place. This is beneficial for community identity and wellbeing as well as making places attractive to investment.

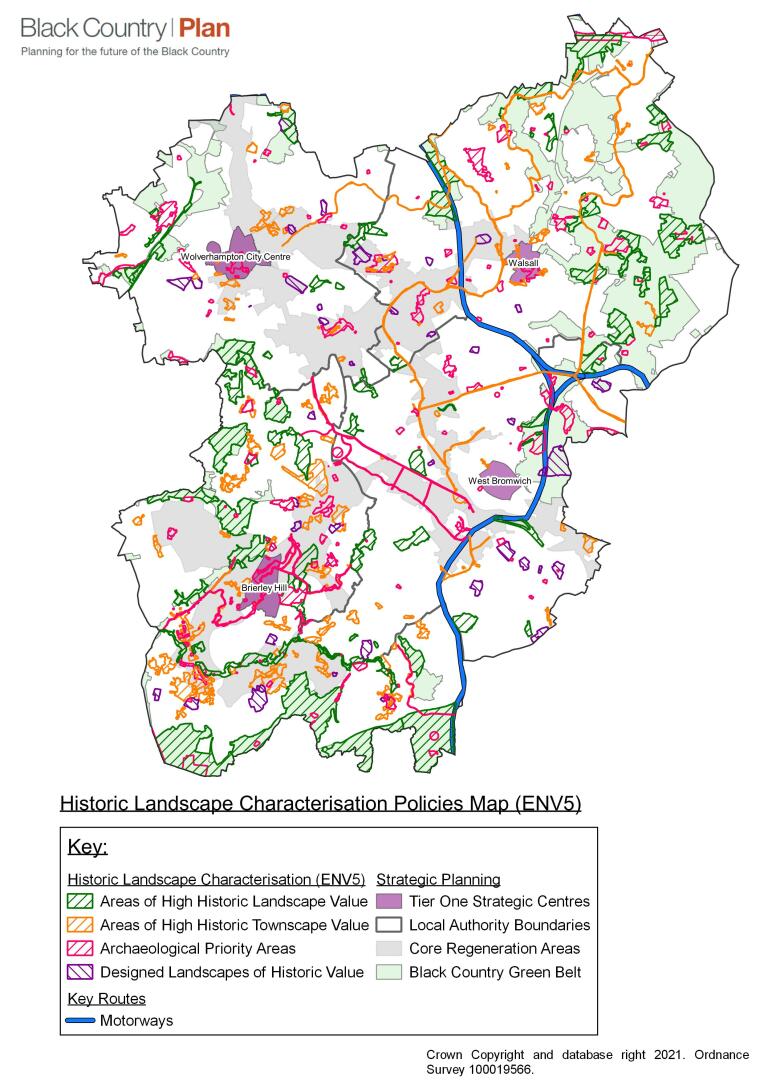

10.77 The Black Country Historic Landscape Characterisation (2009), along with other urban historic landscape characterisation studies, has provided a key evidence base to inform an understanding of the historic character of the Black Country. This work has been built upon with the preparation of the Black Country Historic Landscape Characterisation Study (2019), and this evidence should be used in considering how new development proposals and the enhancement of existing townscapes and landscape should respect the local character and distinctiveness of the Black Country.

10.78 Policy ENV5 aims to ensure that where physical evidence of local character persists, it should be conserved. Where development is proposed, every effort should be made to ensure that the Black Country's historic environment is fully appreciated and enhanced in terms of its townscape, landscape and individual heritage assets, and that new development makes a positive contribution to the local character and distinctiveness of the Black Country.

(38) Policy ENV 5 - Historic Character and Local Distinctiveness of the Black Country

- All development proposals within the Black Country should sustain and enhance the locally distinctive character of the area in which they are to be sited, whether formally recognised as a designated or non-designated heritage asset. They should respect and respond to its positive attributes in order to help maintain the Black Country’s cultural identity and strong sense of place.

- Development proposals will be required to preserve and enhance local character and those aspects of the historic environment - together with their settings - that are recognised as being of special historic, archaeological, architectural, landscape or townscape quality.

- Physical assets, whether man-made or natural that contribute positively to the local character and distinctiveness of the Black County’s landscape and townscape should be retained and, wherever possible, enhanced and their settings respected.

- The specific pattern of settlements (urban grain), local vernacular and other precedents that contribute to local character and distinctiveness should be used to inform the form, scale, appearance, details, and materials of new development.

- New development in the Black Country should be designed to make a positive contribution to local character and distinctiveness and demonstrate the steps that have been taken to achieve a locally responsive design. Proposals should therefore demonstrate that:

- all aspects of the historic character and distinctiveness of the locality, including any contribution made by their setting, and (where applicable) views into, from, or within them, have been fully assessed and used to inform proposals; and

- they have been prepared with full reference to the Black Country Historic Landscape Characterisation Study (BCHLCS) (October 2019), the Historic Environment Record (HER), and to other relevant historic landscape characterisation documents, supplementary planning documents (SPD’s) and national and local design guides where applicable.

- All proposals should aim to sustain and reinforce special character and conserve the historic aspects of locally distinctive areas of the Black Country, for example:

- The network of now coalesced but nevertheless distinct small industrial settlements of the former South Staffordshire Coalfield, such as Darlaston and Netherton;

- The civic, religious, and commercial cores of the principal settlements of medieval origin such as Wolverhampton, Dudley, Wednesbury and Walsall;

- Surviving pre-industrial settlement centres of medieval origin such as Halesowen, Tettenhall, Aldridge, Oldbury and Kingswinford;

- Rural landscapes and settlements including villages / hamlets of medieval origin, relic medieval and post-medieval landscape features (hedgerows, holloways, banks, ditches, field systems, ridge and furrow), post-medieval farmsteads and associated outbuildings, medieval and early post-medieval industry (mills etc.) and medieval and post-medieval woodland (see Policy ENV4). The undeveloped nature of these areas means there is also the potential for evidence of much earlier activity that has largely been lost in the urban areas;

- Areas of Victorian and Edwardian higher-density development, which survive with a high degree of integrity including terraced housing and its associated amenities;

- Areas of extensive lower density suburban development of the mid-20th century including public housing and private developments of semi-detached and detached housing;

- Public open spaces, including Victorian and Edwardian municipal parks, often created from earlier large rural estates or upon land retaining elements of relict industrial landscape features;

- The canal network and its associated infrastructure, surviving canal-side pre-1939 buildings and structures together with archaeological evidence of the development of canal-side industries and former canal routes (see Policy ENV7);

- Buildings, structures and archaeological remains of the traditional manufacturing and extractive industries of the Black Country including glass making, metal trades (such as lock making), manufacture of leather goods, brick-making, coal mining and limestone quarrying;

- Geosites of geological, historic, cultural, and archaeological significance within the UNESCO Black Country Geopark (see Policy ENV6);

- The Beacons and other largely undeveloped high prominences lying along the Sedgley to Northfield Ridge (including Sedgley Beacon and Wrens Nest), Castle Hill and the Rowley Hills (Turners Hill), and the Queslett to Shire Oak Ridge (including Barr Beacon) and views to and from these locations.

- In addition to designated heritage assets[47], attention should be paid to the following non-designated heritage assets[48] including the Historic Environment Area Designations (HEADS) described and mapped in the Black Country Historic Landscape Characterisation Study (BCHLCS, 2019 – see evidence section for link):

- Areas of High Historic Townscape Value (AHHTV) that exhibit a concentration of built heritage assets and other historic features that, in combination, make a particularly positive contribution to local character and distinctiveness;

- Areas of High Historic Landscape Value (AHHLV) that demonstrate concentrations of important wider landscape elements of the historic environment, such as areas of open space, woodland, watercourses, hedgerows, and archaeological features, that contribute to local character and distinctiveness;

- Designed Landscapes of High Historic Value (DLHHV) that make an important contribution to local historic character but do not meet the criteria for inclusion on the national Register for Parks and Gardens;

- Archaeology Priority Areas (APA) that have a high potential for the survival of archaeological remains of regional or national importance that have not been considered for designation as scheduled monuments, or where there is insufficient data available about the state of preservation of any remains to justify a designation;

- Locally listed buildings / structures and archaeological sites;

- Non-designated heritage assets of archaeological interest;

- Any other buildings, monuments, sites, places, areas of landscapes identified as having a degree of significance[49].

- Development proposals that would potentially have an impact on the significance of any of the above distinctive elements, including any contribution made by their setting, should be supported by evidence that the historic character and distinctiveness of the locality has been fully assessed and used to inform proposals. Clear and convincing justification should be provided, either in Design and Access Statements, Statements of Heritage Significance, or other appropriate reports.

- In some instances, local planning authorities will require developers to provide detailed Heritage Statements and / or Archaeological Desk-based Assessments to support their proposals.

- For sites with archaeological potential, local authorities may also require developers to undertake Field Evaluation to support proposals.

Figure 12 - Historic Landscape Characterisation Policies Map[50]

(2) Justification

10.79 The Black Country has a rich and diverse historic environment, which is evident in the survival of individual heritage assets and in the local character and distinctiveness of the broader landscape. The geodiversity of the Black Country underpins much of the subsequent development of the area, the importance of which is acknowledged by the inclusion of the Black Country Geopark in the UNESCO Global Geopark Network[51]. The exploitation of abundant natural mineral resources, particularly those of the South Staffordshire coalfield, together with the early development of the canal network, gave rise to rapid industrialisation and the distinctive settlement patterns that characterise the area.

10.80 Towns and villages with medieval origins survive throughout the area and remain distinct in character from the later 19th century industrial settlements, which typify the coalfield and gave rise to the description of the area as an "endless village" of communities, each boasting a particular manufacturing skill for which many were internationally renowned.

10.81 Beyond its industrial heartland, the character of the Black Country can be quite different and varied. The green borderland, most prominent in parts of Dudley, Walsall, and the Sandwell Valley, is a largely rural landscape containing fragile remnants of the ancient past. Undeveloped ridges of high ground punctuate the urban landscape providing important views and points of reference that define the character of the many communities. Other parts of the Black Country are characterised by attractive, well-tree'd suburbs with large houses in substantial gardens and extensive mid-20th century housing estates designed on garden city principles.

10.82 This diverse character is under constant threat of erosion from modern development, some small scale and incremental and some large scale and fundamental. As a result, some of the distinctiveness of the more historic settlements has already been lost to development of a "homogenising" character. In many ways the Black Country is characterised by its ability to embrace change, but future changes will be greater and more intense than any sustained in the past. Whilst a legislative framework supported by national guidance exists to provide for the protection of statutorily designated heritage assets the key challenge for the future is to manage change in a way that realizes the regeneration potential of the proud local heritage and distinctive character of the Black Country.

10.83 To ensure that heritage assets make a positive contribution towards the wider economic, social and environmental regeneration of the Black Country, it is important that they are not considered in isolation but are conserved and enhanced within their wider context. A holistic approach to the built and natural environment maximises opportunities to improve the overall image and quality of life in the Black Country by ensuring that historic context informs planning decisions and provides opportunities to link with other environmental infrastructure initiatives.

10.84 An analysis and understanding of the local character and distinctiveness of the area has been made using historic landscape characterization (HLC) principles. Locally distinctive areas of the Black Country have been defined and categorised as Areas of High Historic Townscape Value, Areas of High Historic Landscape Value, Designed Landscapes of High Historic Value, and Archaeology Priority Areas (BCHLCS, 2019). This builds on the work of the original Black Country Historic Landscape Characterization (2009), other local HLC studies and plans, and the Historic Environment Records.

(1) Evidence

- Black Country Historic Landscape Characterisation Study (2019) – available online at: https://blackcountryplan.dudley.gov.uk/t2/p4/t2p4h/ Black Country HLC Final Report 30-10-2019-LR

- Historic Environment Record (HER)

- https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/national-design-guide .

(2) Delivery

- Historic Landscape Characterisation documents prepared by individual local authorities in support of their Local Plan

- Adopted Conservation Area Character Appraisals

- Development Management process including Design and Access Statements and Statements of Heritage Significance

- Supplementary Planning Documents

- A regularly updated and maintained Historic Environment Record (HER).

Issues and Options consultation responses

10.85 Among the issues raised during the consultation, the idea of a heritage policy was broadly supported. The importance of Heritage Statements, and non-designated heritage assets was noted. Greater recognition of nature and natural features in terms of local distinctiveness and historic character was sought, and concerns were expressed about impacts on the Green Belt.

Geodiversity and the Black Country UNESCO Global Geopark

10.86 The geology of the Black Country is very rich in industrial minerals. Limestone, ironstone, fireclay, coal and other industrial minerals provided the ingredients to make iron and paved the way for an intense and very early part of the Industrial Revolution to begin in the area.

10.87 The Black Country UNESCO Global Geopark was declared on Friday 10 July 2020. The Executive Board of UNESCO confirmed that the Black Country had been welcomed into the network of Global Geoparks as a place with internationally important geology, because of its cultural heritage and the extensive partnerships committed to conserving, managing and promoting it.

10.88 A UNESCO Global Geopark uses its geological heritage, in connection with all other aspects of the area's natural and cultural heritage, to enhance awareness and understanding of key issues facing society in the context of the dynamics of modern society, mitigating the effects of climate change and reducing the impact of natural disasters. By raising awareness of the importance of the area's geological heritage in history and society today, UNESCO Global Geoparks give local people a sense of pride in their region and strengthen their identification with the area. The creation of innovative local enterprises, new jobs and high-quality training courses is stimulated as new sources of revenue are generated through sustainable geotourism, while the geological resources of the area are protected.

(7) Policy ENV6 - Geodiversity and the Black Country UNESCO Global Geopark

- Development proposals should:

- wherever possible, make a positive contribution to the protection and enhancement of geodiversity, particularly within the boundaries of the Black Country UNESCO Global Geopark and in relation to the geosites identified within it;

- be resisted where they would have significant adverse impact on the Geopark geosites or other sites with existing or proposed European or national designations in accordance with Government guidance;

- give locally significant geological sites[52] a level of protection commensurate with their importance;

- take into account, and avoid any disruption to, the importance of the inter-connectivity of greenspace and public access between geosites within the boundary of the Black Country UNESCO Global Geopark.

- In their local plans, the BCA should:

- establish clear goals for the management of identified sites (both individually and as part of a network) to promote public access to, appreciation and interpretation of geodiversity;

- ensure geological sites of international, national or regional importance are clearly identified.

(1) Justification

10.89 Paragraph 170 of the NPPF (June 2019) requires local authorities to protect sites of geological value, "… in a manner commensurate with their statutory status or identified quality in the development plan". The Overarching National Policy Statement for Energy[53] states that development should aim to avoid significant harm to geological conservation interests and identify mitigation where possible; effects on sites of geological interest should be clearly identified.

10.90 Areas of geological interest also form significant facets of the industrial landscapes of the Black Country. They reflect the area's history of mining and extraction and will often co-exist with, and form part of the setting of, protected / sensitive historic landscapes. In many cases they also form an intrinsic part of the green infrastructure network, contributing to landscape and ecological diversity as part of the wider natural environment.

10.91 As part of this strategic network of green infrastructure, geosites should be retained wherever possible and their contribution to GI recognised and taken into account when development is proposed that would affect the areas they form part of.

10.92 New development should have regard to the conservation of geological features and should take opportunities to achieve gains for conservation through the form and design of development.

10.93 Where development is proposed that would affect an identified geological site the approach should be to avoid adverse impact to the existing geological interest. If this is not possible, the design should seek to retain as much as possible of the geological Interest and enhance this where achievable, for example by incorporating permanent sections within the design, or creating new interest of at least equivalent value by improving access to the interest.

10.94 The negative impacts of development should be minimised, and any residual impacts mitigated.

UNESCO Global Geoparks

10.95 A UNESCO Global Geopark[54] is a single, unified geographical area where sites and landscapes of international geological significance are located. It is an area of geological significance, managed with three main objectives in mind:

a) to protect the geological landscape and the nature within it;

b) to educate visitors and local communities; and

c) to promote sustainable development, including sustainable tourism.

10.96 All the UNESCO Global Geoparks contain internationally significant geology and are managed through community-led partnerships that promote an appreciation of natural and cultural heritage while supporting the sustainable economic development of the area.

10.97 UNESCO Global Geopark status is not itself a statutory designation.

Evidence

Delivery

- Geopark Management Team, delivering aims of the Geopark

Issues and Options Consultation Responses

10.98 This is a new policy produced in response to the Black Country Geopark being declared by UNESCO in July 202 and was not subject to consultation during issues and options.

Canals of the Black Country

10.99 The Black Country's canal network is one of its most defining historical and environmental assets and its preservation and enhancement remains a major objective in the Vision for environmental transformation across the area and in the delivery of Strategic Priorities 11 and 12. Canals play a multifunctional role, providing economic, social, environmental and infrastructure benefits. They form a valuable part of the green infrastructure and historic environment of the Black Country and have a significant role to play in mental wellbeing and physical health, allowing people opportunities for exercise and access to nature.

(23) Policy ENV7 - Canals

- The Black Country canal network comprises the canals and their surrounding landscape corridors, designated and undesignated historic assets, character, settings, views and interrelationships. The canal network provides a focus for future development through its ability to deliver a high-quality environment and enhanced accessibility for pedestrians, cyclists, and other non-car-based modes of transport.

- All development proposals likely to affect the canal network must:

- safeguard the continued operation of a navigable and functional waterway;

- ensure that any proposals for reinstatement or reuse would not adversely impact on locations of significant environmental value where canals are not currently navigable;

- protect and enhance its special historic, architectural, archaeological, and cultural significance, including the potential to record, preserve and restore such features;

- protect and enhance its nature conservation value including habitat creation and restoration along the waterway and its surrounding environs;

- protect and enhance its visual amenity, key views and setting;

- protect and enhance water quality in the canal.

- reinstate and / or upgrade towpaths and link them into high quality wider pedestrian and cycle networks, particularly where they can provide links to transport hubs, centres and opportunities for employment.

- Where opportunities exist, all development proposals within the canal network must:

- enhance and promote its role in providing opportunities for leisure, recreation and tourism activities;

- enhance and promote opportunities for off-road walking, cycling, and boating access, including for small-scale commercial freight activities;

- preserve and enhance the historical, geological, and ecological value of the canal network and its associated infrastructure;

- positively relate to the opportunity presented by the waterway by promoting high quality design, including providing active frontages onto the canal and by improving the public realm;

- sensitively integrate with the canal and any associated canal-side features and, where the opportunities to do so arises, incorporate canal features into the development.

- Development proposals must be fully supported by evidence that the above factors have been fully considered and properly incorporated into their design and layout.

- Where proposed development overlays part of the extensive network of disused canal features, the potential to record, preserve and restore such features must be fully explored. Development on sites that include sections of disused canals should protect the line of the canal through the detailed layout of the proposal. Development will not be permitted that would sever the route of a disused canal or prevent the restoration of a canal link where there is a realistic possibility of restoration, wholly or in part.

Residential Canal Moorings

- For residential moorings, planning consent will only be granted for proposals that include the provision of:

- the necessary boating facilities (a minimum requirement of electrical power, a water supply and sanitary disposal);

- dedicated car parking provided within 500m of the moorings, suitable vehicular access, including access by emergency vehicles and suitable access for use by people with disabilities;

- appropriate access to cycling and walking routes;

- an adequate level of amenity for boaters, not unduly impacted upon by reason of noise, fumes or other nearby polluting activities.

- In determining a planning application for residential moorings, account will be taken of the effect that such moorings and their associated activities may have on the amenities or activities of nearby residential or other uses.

(2) Justification

10.100 The development of the Black Country's canal network had a decisive impact on the evolution of industry and settlement during the 18th, 19th, and 20th centuries. It was a major feat of engineering and illustrates a significant stage in human history - development of mercantile inland transport systems in Britain's industrial revolution during the pre-railway age. As such, the historic value of the Black Country's canal network today should be acknowledged, promoted, protected, and enhanced. The network also plays a major part in the Black Country Geopark, as the mineral wealth of the area meant that canals were a vital link to areas within and beyond the Black Country and continue to provide this link today.

10.101 The canal network is a major unifying characteristic of the Black Country's historic landscape. The routes of the canals that make up the network have created landscape corridors with a distinctive character and identity based on the industries and activities that these transport routes served and supported. The network has significant value for nature conservation, tourism, health and wellbeing and recreation and the potential to make an important contribution to economic regeneration through the provision of high-quality environments for new developments and a network of pedestrian, cycle and water transport routes.

10.102 It is also important for development in the Black Country to take account of disused canal features, both above and below ground. Only 54% of the historic canal network has survived in use to the present day; a network of tramways also served the canals. Proposals should preserve the line of the canal through the detailed layout of the development. Where appropriate, opportunities should be explored for the potential to preserve the line of the canal as part of the wider green infrastructure network. Where feasible and sustainable, proposals should consider the potential for the restoration of disused sections of canal.

10.103 It is acknowledged that there are aspirations to restore disused sections of the canal network within the Black Country. However, it is also recognised that there are very limited opportunities to reinstate such canal sections as navigable routes because of the extensive sections that have been filled in, built over or removed making their reinstatement (and necessary original realignment) financially unviable and unachievable within the Plan period.

10.104 There are also areas within the disused parts of the canal network that have naturally regenerated into locations with significant ecological and biodiversity value; to re-open or intensify use on these sections of the network could have an adverse impact on sensitive habitats and species.

10.105 Any development proposals that come forward to restore sections of the canal network will be expected to demonstrate that the proposals are sustainable, sufficient water resources exist, and that works will not adversely affect the existing canal network or the environment.

10.106 Residential moorings must be sensitive to the needs of the canalside environment in conjunction with nature conservation, green belt and historic conservation policies but also, like all residential development, accord with sustainable housing principles in terms of design and access to local facilities and a range of transport choices.

(1) Evidence

- Black Country Historic Landscape Characterisation Study (2019)

- Historic Landscape Characterisation documents prepared by individual local authorities in support of their Local Plan

- Adopted Conservation Area Character Appraisals

- Historic England Good Practice Advice Notes (GPAs) and Historic England Advice Notes (HEANs)

Issues and Options consultation responses