- 1 Introduction

- 2 The Black Country 2039: Spatial Vision, Strategic Objectives and Strategic Priorities

- 3 Spatial Strategy

- 4 Infrastructure & Delivery

- 5 Health and Wellbeing

- 6 Housing

- 7 The Black Country Economy

- 8 The Black Country Centres

- 9 Transport

- 10 Environmental Transformation and Climate Change

- 11 Waste

- 12 Minerals

- 1 Sub-Areas and Site Allocations

- 2 Delivery, Monitoring, and Implementation

- 3 Appendix – changes to Local Plans

- 4 Appendix – Centres

- 5 Appendix – Black Country Plan Housing Trajectory

- 6 Appendix – Nature Recovery Network

- 7 Appendix – Glossary (to follow)

Draft Black Country Plan

(12) 5 Health and Wellbeing

Introduction

5.1 The purpose of the planning system in England is to contribute to the achievement of sustainable development. The built and natural environments are key determinants of health and wellbeing. The NPPF states that one of the three overarching objectives of the planning system is supporting strong, vibrant, and healthy communities. The Health and Social Care Act (2012) gave local authorities new duties and responsibilities for health improvement and requires every local authority to use all levers at its disposal to improve health and wellbeing; Local Plans are one such lever.

5.2 Planning policies and decisions should make sufficient provision for facilities such as health infrastructure and aim to achieve healthy, inclusive, and safe places that support healthy lifestyles, especially where they address identified local health and well-being needs. Engagement between Local Planning Authorities and relevant organisations will help ensure that local development documents support both these aims.

5.3 The Black Country's unique circumstances give rise to several challenges to health and well-being, which are reflected in its related strategies. Ensuring a healthy and safe environment that contributes to people's health and wellbeing is a key objective of the Black Country Councils and their partners in the health, voluntary and other related sectors.

5.4 The Black Country Local Planning Authorities, Public Health Departments, Hospital Trusts and Clinical Commissioning Groups have worked together in preparation for the Black Country Plan, to ensure it is aligned with the plans of the area's Sustainability and Transformation Partnership (STP), as well as with each borough's Health and Wellbeing Strategies, informed by their Joint Strategic Needs Assessments.

5.5 The STP recognises that reducing health inequalities will help reduce financial burdens on the NHS. It also recognises that residents of the Black Country, on average, suffer from poorer health outcomes than people in the rest of England.

5.6 The STP has identified a number of key drivers that play a significant role in the development of future illness in the Black Country and which directly link to demand for health provision. These are education, employment, wealth, housing, nutrition, family life, transport and social isolation. These are all influenced by the built and natural environment.

Linkages between health and the built and natural environment

5.7 The linkages between health and the built and natural environment are long established and the role of the environment in shaping the social, economic, and environmental circumstances that determine health is increasingly recognised and understood. Climate change will have a negative impact on health and wellbeing and actions to eliminate emissions and adapt to climate change, such as promoting active travel and improving the energy efficiency of buildings, will also benefit public health through outcomes such as reduced obesity and fuel poverty.

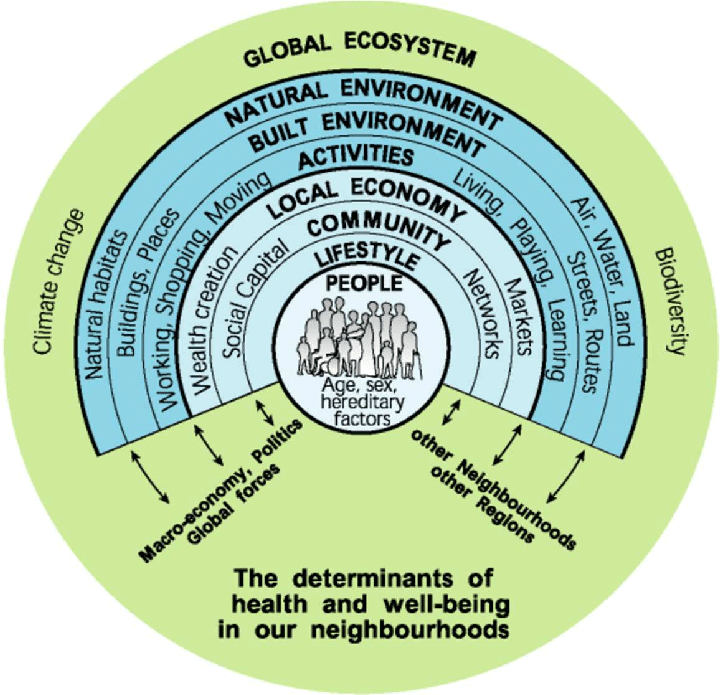

5.8 An increasing body of research indicates that the environment in which people live is linked to health across their lifetime. For example, the design of neighbourhoods can influence physical activity levels, travel patterns, social connectivity, food consumption, mental and physical health, and wellbeing outcomes. These are illustrated below in the Barton and Grant (2010) Health Map.

Figure 3 - Determinants of health and wellbeing (Barton and Grant, 2010)

5.9 As outlined in more detail below, the evidence from the Sustainability and Transformation Partnership suggests that the Black Country performs worse than the England average with regards to risk factors for poor health outcomes that are linked to the built and natural environment. For example, the Black Country has lower rates of physical activity and higher rates of obesity. Poor air quality is harmful to health and unhealthy fast food is easily available. In the home, rates of falls and hip fractures in older people are high, as are households living in fuel poverty, meaning people are exposed to the risk of cold housing in winter thereby exacerbating long-term conditions.

5.10 The Black Country has lower rates of both life expectancy and healthy life expectancy than the rest of England, meaning people not only die earlier but live more of their life with ill health, which has implications for their ability to be productive and for how they use the built and natural environment. On a broader level, the Black Country has higher rates of multiple deprivation, of children living in poverty and of unemployment than the rest of England, as well as some of the poorest academic achievement of school leavers. These factors all contribute to poorer health outcomes and are influenced by the built and natural environment.

5.11 The Black Country also has higher of rates of admissions for alcohol and higher depression rates compared to the England average. Many users of adult social care say they feel socially isolated and experience poor health-related quality of life.

5.12 The Black Country's Health and Wellbeing Strategies identify the following as key priorities for tackling health and wellbeing:

a) Healthy lifestyles including physical activity, healthy eating, and addressing tobacco and alcohol consumption and obesity;

b) Access to employment, education, and training;

c) Quality, affordable homes that people can afford to heat;

d) Mental health and wellbeing, including having social connections and feeling lonely or isolated;

e) Air quality and the wider environment.

5.13 There is therefore a need for the BCP to support initiatives aimed at encouraging healthier lifestyle choices and mental wellbeing and addressing socio-economic and environmental issues that contribute to poor health and inequalities.

Health and Wellbeing

5.14 This policy provides a strategic context for how health and wellbeing are influenced by planning and provides links to other policies in the Black Country Plan.

(49) Policy HW1 – Health and Wellbeing

- The regeneration and transformation of the Black Country will create an environment that protects and improves the physical, social and mental health and wellbeing of its residents, employees and visitors and reduces health inequalities through ensuring that all new developments, where relevant:

- are inclusive, safe, and attractive, with a strong sense of place; encourage social interaction; and provide for all age groups and abilities as set out in Policies CSP4, ENV5, ENV6, ENV8 and ENV9;

- are designed to enable active and healthy lives through prioritising access by inclusive, active, and environmentally sustainable form of travel and through promoting road safety and managing the negative effects of road traffic as set out in Policies CSP4 and TRAN2, TRAN4 and TRAN5;

- provide a range of housing types and tenures that meet the needs of all sectors of the population including for older people and those with disabilities requiring varying degrees of care; extended families; low income households; and those seeking to self-build as set out in Polices HOU2 and HOU3;

- are energy efficient and achieve affordable warmth; provide good standards of indoor air quality and ventilation; are low carbon; mitigate against climate change; and are adapted to the effects of climate change as set out in Policies CSP4, ENV9, CC1, CC2, CC3 and CC7;

- are designed and located to achieve acceptable impacts by developments on residential amenity and health and wellbeing arising from: noise; ground and water contamination; flood risk; vibration; and poor indoor and outdoor air quality as set out in Policies CSP4, ENV9, CC4, CC5, MIN4 and TRAN7;

- provide a range of quality employment opportunities for all skillsets and abilities along with the education and training facilities to enable residents to fulfil their potential and support initiatives to promote local employment and procurement during construction as set out in Policies HOU5, EMP2, EMP3 and EMP5;

- protect and include a range of social infrastructure such as social care, health, leisure, sport and recreation, retail and education facilities close to where people live, which are accessible by means of inclusive, active and environmentally sustainable forms of travel as set out in Policy HOU5;

- protect, enhance, and provide new green and blue infrastructure, sports facilities, play and recreation opportunities to support access for all and meet identified needs as set out in Policies CSP4 and ENV4, ENV6, ENV7 and ENV8;

- protect, enhance, and provide allotments and gardens for physical activity, mental wellbeing, recreation and for healthy locally-produced food as set out in Policy ENV8;

- provide high-quality broadband and other digital services to homes, educational facilities, employers, and social infrastructure, to support digital inclusion and the application of new technology to improved health care as set out in Policy DEL3;

- support vibrant centres and local facilities, which offer services and retail facilities that promote choice, enable and encourage healthy choices and protect children, other young people, and vulnerable adults. Where national and local evidence exist, this will include managing the location, concentration of and operation (including opening hours) of businesses which contain uses running contrary to these aims including (but not restricted to) establishments selling hot food, shisha bars, drinking establishments, amusement arcades, betting shops and payday loan outlets as set out in Policies CEN1 - CEN6 (inclusive).

(3) Justification

5.15 The Black Country Plan encourages planning decisions that help improve the overall health and wellbeing of residents and help people to lead healthier lives more easily. The aim of the policy is to improve the health impacts of new developments and minimise negative impacts. Improving the health of residents helps to reduce the burden on the National Health Service, thereby providing society with wider economic benefits.

5.16 Evidence shows that important determinants of health include:

a) inclusive and secure environments;

b) physical activity including active travel;

c) quality homes;

d) good air quality and appropriately low-level noise environments;

e) access to education and employment opportunities;

f) access to services and to green spaces;

g) healthy eating;

h) digital inclusion;

i) reducing exposure to harmful and addictive behaviour.

This means that addressing health inequalities will need a comprehensive approach and joint working across various services to achieve desired outcomes.

5.17 The Marmot Review (February 2010) highlighted that socio-economic inequalities, including the built environment, have a clear effect on the health outcomes of the population. One of the key policy objectives aimed at reducing the gap in life expectancy between people of lower and higher socio-economic backgrounds, is to "create and develop healthy and sustainable places and communities".

5.18 In February 2020 The Institute of Health Equity published The Health Foundation's Health Equity in England: The Marmot Review 10 Years On. The report highlights that poor health is increasing, the health gap has grown between wealthy and deprived areas and that place matters to health. The review goes on to recommend:

- Investment in the development of economic, social and cultural resources in the most deprived communities

- 100% of new housing to be carbon neutral by 2030, with an increased proportion being either affordable or in the social housing sector

- Aim for net zero carbon emissions by 2030 ensuring inequalities do not widen as a result

5.19 Many of these issues are addressed in the wider policies of the Black Country Plan as indicated in the policy text, although it is important to underline here the role of these policies in addressing the wider determinants of health.

5.20 As outlined above, residents of the Black Country suffer from poorer health outcomes than the rest of England, across a broad range of indicators. The evidence from Public Health England and elsewhere suggests that the Black Country also performs worse with regards to risk factors for poor health outcomes that are linked to the built environment. Obesity is considered a risk factor for cancer and diabetes and maternal obesity is a risk factor for infant mortality. The Black Country has higher rates of physically inactive adults and children and higher rates of obesity than those for England as well as lower rates of the population eating 'five a day' and a higher number of fast food outlets per 100,000 population.

5.21 The Black Country has higher rates of alcohol-related mortality than England, while some BCAs have higher rates of both smoking and of smoking-attributable mortality than England. All areas of the Black Country have higher rates of adults with mental health problems than for England as a whole.

5.22 Providing and improving a range of open space and sports and leisure facilities for physical activity, including active travel, are key to tackling obesity and improving physical and mental health and wellbeing. The protection and provision of allotments and other forms of urban horticulture provides the additional benefit of supporting healthy eating. Individual Black Country Authorities may also wish to introduce planning restrictions on uses that have a negative effect upon the population's health.

5.23 People with gambling problems often experience a range of negative effects including health issues, relationship breakdown and debt plus, in more severe cases, resorting to crime or suicide. Because of this, there are increasing calls for gambling to be recognised as a public health issue. Financial problems can themselves be a significant source of distress, putting pressure on people's mental health. There are also strong causal links from mental health problems to financial difficulties.

5.24 There is currently no evidence to show that problem gambling is worse in the Black Country than for England as a whole. There is also no evidence that debt problems arising from payday loan companies are worse than for England. Given the danger which is posed to health and wellbeing by gambling and uncontrolled debt, individual Black Country Authorities may wish to introduce planning restrictions on betting shops, amusement arcades and payday loan shops should local evidence support this, during the lifetime of the Plan. Such measures would be as part of a wider strategy to address these issues.

(1) Evidence

- Dudley Health and Wellbeing Strategy, 2017-22, Dudley Health & Wellbeing Board

- Joint Health and Wellbeing Strategy 2016-2020, Sandwell Health and Wellbeing Board

- The Walsall Plan: Our Health and Wellbeing Strategy 2019-2021, Walsall Partnership

- Wolverhampton Joint Health & Wellbeing Strategy 2018-2023, City of Wolverhampton Health & Wellbeing Together

- STP Primary Care Strategy 2019/20 to 2023/24, Black Country and West Birmingham Sustainability and Transformation Partnership (STP), June 2019 (updated November 2019)

- A health map for the local human habitat, H. Barton & M. Grant, Journal of the Royal Society for the Promotion of Health, 2006

- Fair Society, Healthy Lives: The Marmot Review - Strategic Review of Health Inequalities in England post-2010, Institute of Health Equity, 2010

- Health Equity in England: The Marmot Review 10 Years On, Institute of Health Equity, 2020

- Planning for Health in the Black Country: Evidence Base for Black Country Plan Health and Wellbeing Chapter, 2021

Delivery

- Through Development Management, tier two Development Plan Documents and Supplementary Planning Documents

- Implementation and funding will be sought through planning conditions, planning agreements and planning obligations as well as through external funding sources

Issues and Options Consultation Responses

- There was support for incorporating health and wellbeing in the Core Strategy review and for it having its own policy, as well as being embedded into other policies which further acknowledge the wider determinants of health.

Specific suggestions included:

- The need to give due consideration to the health needs and demographics of the local area

- Design standards that promote safety as well as healthy lifestyles and environments across the life course.

- Addressing congestion and air pollution.

- The need to make the Black Country an attractive location for people and businesses by creating a pleasant environment and offering an excellent quality of life.

- Greater reference to existing green infrastructure and improved provision of public open space, including the canal network, because of the opportunities they provide for exercise, leisure, recreation and sporting activities and improvements in the quality of life.

- Encouragement of walking and cycling, provision of traffic free routes, traffic restraint and pedestrianisation.

- Juxtaposition of land-uses to encourage better home / job relationships including the promotion of working from home.

Healthcare Infrastructure

5.25 This policy sets out the requirements for the provision of health infrastructure to serve the residents of new developments in support of Policies HW1 and HW3.

(17) Policy HW2 – Healthcare Infrastructure

- New healthcare facilities should be:

- well-designed and complement and enhance neighbourhood services and amenities;

- well-served by public transport infrastructure, walking and cycling facilities and directed to a centre appropriate in role and scale to the proposed development, and its intended catchment area, in accordance with Policies CEN1, CEN2, CEN3 and CEN4. Proposals located outside centres must be justified in terms of relevant BCP policies such as CEN5 and CEN6, where applicable;

- wherever possible, located to address accessibility gaps in terms of the standards set out in Policy HOU2, particularly where a significant amount of new housing is proposed;

- where possible, co-located with a mix of compatible community services on a single site.

- Existing primary and secondary healthcare infrastructure and services will be protected, and new or improved healthcare facilities and services will be provided, in accordance with requirements agreed between the Local Panning Authorities and local health organisations, which will be contained in local development documents.

- Proposals for major residential developments of ten units or more must be assessed against the capacity of existing healthcare facilities and/or services as set out in local development documents. Where the demand generated by the residents of the new development would have unacceptable impacts upon the capacity of these facilities, developers will be required to contribute to the provision or improvement of such services, in line with the requirements and calculation methods set out in local development documents.

- Where it is not possible to address such provision through planning conditions, a planning agreement or planning obligation may be required.

- In the first instance, infrastructure contributions will be sought to deal with relevant issues on the site or in its immediate vicinity. Where this is not possible, however, or the sequential test is not met by the site, an offsite (commuted) contribution will be negotiated. Other contributions may include for offsite provision of health or related services.

- The effects of the obligations on the financial viability of development may be a relevant consideration.

- For strategic sites, the likely requirement for on-site provision for new health facilities is set out in Chapter 13.

(1) Justification

5.26 Meeting the Black Country's future housing needs will have an impact on existing healthcare infrastructure and generate demand for both extended and new facilities across the Plan area, as well as impacting upon service delivery as population growth results in additional medical interventions in the population.

5.27 Health Services in the Black Country are currently experiencing limitations on their physical and operational capacity, which inhibit their ability to respond to the area's health needs.

5.28 The BCA and their partners, including other healthcare infrastructure providers, have a critical role to play in delivering high-quality services and ensuring the Black Country's healthcare infrastructure amenities and facilities are maintained, improved and, where necessary, expanded[8]. Healthcare infrastructure planning is necessarily an on-going process and the Councils will continue to work closely with these partners and the development industry to assess and meet existing and emerging healthcare infrastructure needs.

5.29 As the Black Country grows and changes, social and community facilities must be developed to meet the changing needs of the region's diverse communities. This will in turn mean that, new improved and expanded healthcare facilities will be required. It is proposed to support and work with the NHS and other health organisations to ensure the development of health facilities where needed in new development areas. Where appropriate, these will be included in Local Development Documents and masterplans. It is also proposed to explore the co-location of health and other community facilities such as community centres, libraries and sport and recreation facilities.

5.30 Funding for many healthcare infrastructure projects will be delivered from mainstream NHS sources, but for some types of infrastructure, an element of this funding may also include contributions from developers. This may relate to the provision of physical infrastructure, such as premises, or social infrastructure, such as the delivery of additional services. These contributions would be secured through planning agreements or planning obligations, in line with the relevant regulations in operation at the time; these are currently the Community Infrastructure Levy (CIL) Regulations 2010 (as amended). In line with the sequential test, as set out in the latest national guidance and any local guidance or requirements in tier-two plans, contributions will be sought initially to support infrastructure on-site, with alternatives being considered where this is not possible, or the sequential test is not met by the site.

5.31 In establishing the need for and level of any developer contribution, residential developments will be assessed against the ability of nearby primary, secondary and community healthcare provision to be delivered without being compromised by demand from additional residents. Assessment of the capacity of existing healthcare facilities to meet the demand generated by residents of new development uses an established method adopted by the Clinical Commissioning Group. Applicants should consult the CCG in advance of the submission of a planning application where a significant amount of housing is to be provided. It is proposed to produce separate guidance on the methodology used for calculating the appropriate level of developer contribution.

5.32 The Viability and Delivery Study indicates that, depending on the extent of other planning obligations required, such contributions may not be viable on some sites, particularly those located in lower value zones as shown on Figure 6. Where it can be proved that it is not viable for a housing developer to fund all its own healthcare needs, alternative funding sources will be sought.

Evidence

- STP Primary Care Strategy 2019/20 to 2023/24, Black Country and West Birmingham Sustainability and Transformation Partnership (STP), June 2019 (updated November 2019)

- The Black Country STP Draft Estates Strategy, Black Country and West Birmingham Sustainability and Transformation Partnership, July 2018

- Summer 2019 STP/ICS Estates Strategy Check-point Return, Black Country and West Birmingham Sustainability and Transformation Partnership, July 2019

- Health Infrastructure Strategy, Dudley Clinical Commissioning Group, May 2016

- Primary Care Estates Strategy 2019 to 2024, Wolverhampton Clinical Commissioning Group, August 2019

- Primary Care Estates Strategy 2019 to 2024, Walsall Clinical Commissioning Group, May 2019

- Estates Strategy 2019 to 2024, Sandwell & West Birmingham Clinical Commissioning Group, October 2019

- Planning for Health in the Black Country: Evidence Base for Black Country Plan Health and Wellbeing Chapter, 2021

Delivery

- Through Development Management and a Supplementary Planning Document

- Implementation and funding will be sought through planning conditions, planning agreements and planning obligations

Issues and Options Consultation Responses

There were no comments relevant to this policy.

Health Impact Assessments

5.33 This policy provides for the individual Black Country authorities to require Health Impact Assessments for development proposals, in line with locally determined criteria, to be set out in local development documents.

(9) Policy HW3 – Health Impact Assessments (HIAs)

- Where required in individual Local Planning Authorities’ local development documents, development proposals will be required to demonstrate that they would have an acceptable impact on health and wellbeing through either a Health Impact Assessment (HIA) or Health Impact Assessment Screening Report, as specified in the relevant local development document.

- Where a development has significant negative impacts on health and wellbeing, the Council may require applicants to provide for mitigation of, or compensation for, such impacts in ways to be set out in the individual Local Planning Authorities’ local development documents. Where it is not possible to provide such mitigation or compensation through planning conditions, a planning agreement or planning obligation may be required.

(1) Justification

5.34 A Health Impact Assessment (HIA) can be a useful tool in assessing development proposals where there are expected to be significant impacts on health and wellbeing. They should be used to reduce adverse impacts and maximise positive impacts on the health and wellbeing of the population, as well as to reduce health inequalities, through influencing the wider determinants of health. This may include provision of infrastructure for health services or for physical activity, recreation, and active travel. HIAs help to achieve sustainable development by finding ways to create a healthy and just society and to enhance and improve the places where people live.

5.35 HIAs can be carried out at any stage in the development process but are best undertaken at the earliest stage possible. This should ideally be prior to the submission of planning applications, to ensure that health and wellbeing issues are considered and addressed fully at the outset. Where this is not appropriate, they should form part of the material submitted to support the relevant planning application. This can be provided as a stand-alone assessment or as part of a wider Sustainability Appraisal (SA), Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA), or Integrated Impact Assessment (IIA).

5.36 Health Impact Assessments (HIAs) and HIA Screenings should be carried out as required in local development documents adopted by individual Local Planning Authorities.

Primary Evidence

- Fair Society, Healthy Lives: The Marmot Review - Strategic Review of Health Inequalities in England post-2010, Institute of Health Equity, 2010

- Health Equity in England: The Marmot Review 10 Years On, Institute of Health Equity, 2020

- Planning for Health in the Black Country: Evidence Base for Black Country Plan Health and Wellbeing Chapter, 2021

- Health Impact Assessment in spatial planning, a guide for local authority public health and planning teams, Public Health England, October 2020

Delivery

- Through Development Management, tier two Development Plan Documents and Supplementary Planning Documents produced by individual Black Country Authorities

Issues and Options Consultation Responses

5.37 There was support for the use of Health Impact Assessment to consider the potential health impacts of developments, including involvement from Public Health teams. One respondent suggested that this should include design standards that promote healthy lifestyles and environments across the life course addressing areas such as: lifetime neighbourhoods; identification of an ideal high street retail offer; consideration of fully pedestrianising town centres; sustainable transport and green infrastructure networks.

Monitoring

|

Policy |

Indicator |

Target |

|

HW1 |

Compliance with supportive policies quoted Compliance with more detailed supportive Development Plan Documents and Supplementary Planning Documents produced by each Black Country Authority |

All developments within scope of the policies All developments within scope of the policies |

|

HW2 |

Location of infrastructure in compliance with the requirements outlined in the policy Receipt of developer contributions where required to support new residential developments |

All developments for health infrastructure All developments for health infrastructure to meet demand generated by new housing developments where contributions are required (subject to viability) |

|

HW3 |

Number of Health Impact Assessments produced |

All developments where required by local development plan documents |

|

Number of recommendations from Health Impact Assessments implemented |

All developments where recommendations are made |

[8] The infrastructure strategies of these partner organisations have helped inform this policy.